Over one hundred years after the phenomenon of global warming first appeared in the media, it is now recognised that carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions to the atmosphere are the leading cause of global warming and, subsequently, climate change. Central to raising awareness of the dangers of global warming, news outlets connect technical-scientific research and the public. Their stories, reports, and commentaries galvanise people into action and pressurise policy to change.

The media and personal experiences are major factors in shaping the public’s perception of risk and the dangers of greenhouse gas emissions. This, in turn, has direct implications for the success of efforts to counter the predicted rise in temperatures. In recognising the media’s key role in covering global events and its ability to influence public opinion, we have used AMPLYFI’s AI-driven insights platform to investigate the extent to which news reporting could skew our perceptions of harmful atmospheric emissions. Our analysis sought to quantify the extent to which global news coverage is either aligned or at odds with actual reported country-level emissions data. Our technology delivers unique insights by utilising AI to analyse both structured and unstructured data at scale in order to uncover previously hidden links, trends, threats, and opportunities.

During the recent COP26 Climate Summit held in Glasgow, media outlets provided a detailed account of the event and the various pledges made by individual countries. In addition to these pledges, leading UK media companies, understanding their role in shaping public opinion, also made a Climate Content Pledge. Major news organisations such as the BBC, ITV, Channel 4 and Sky, committed to ‘increase content that reflects the realities of climate change and highlight solutions around reducing carbon emissions to net zero’. Action will focus on ensuring that their output will be informed by science and recognise the importance of presenting fair and balanced representations of visions for a sustainable future. It is a recognition by the media industry of the importance of reporting the facts on climate change and how it could be damaging to not do so. In our research, we have analysed a vast corpus of news reports produced globally by English language news agencies that discuss CO2 emissions. The analysis was conducted on the last five year’s worth of global news, showing a recent view of news coverage around emissions. Using the data from the analysis, we have compared their reporting to actual scientific data on harmful emissions by region and country.

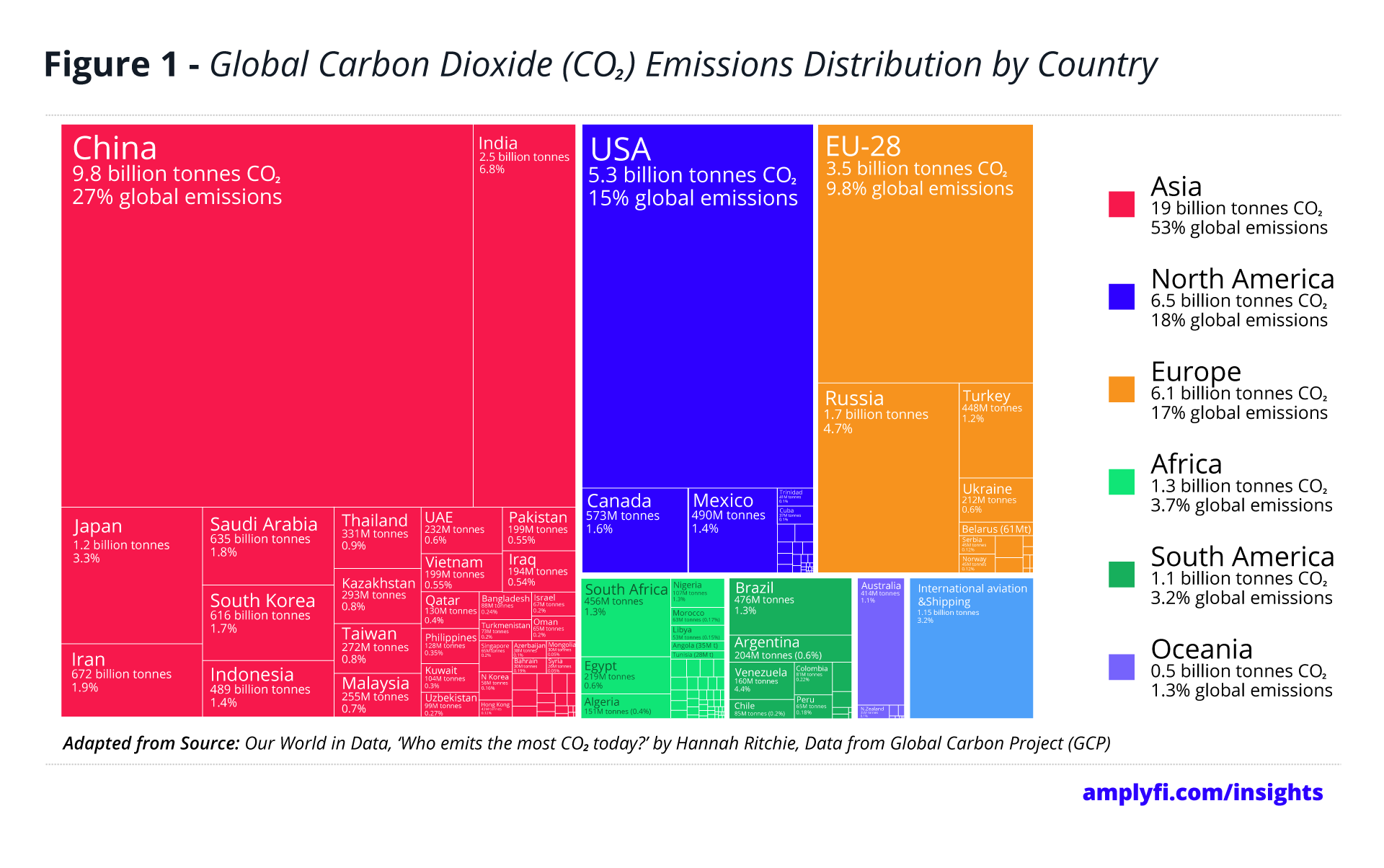

Data from OurWorldinData (see Figure 1 below) shows the distribution of global CO2 emissions by country. It reveals that Asia accounts for just over half of the total. Globally, China is the most heavily polluting country, followed by the USA. As a group, the EU accounts for around 10% of the total.

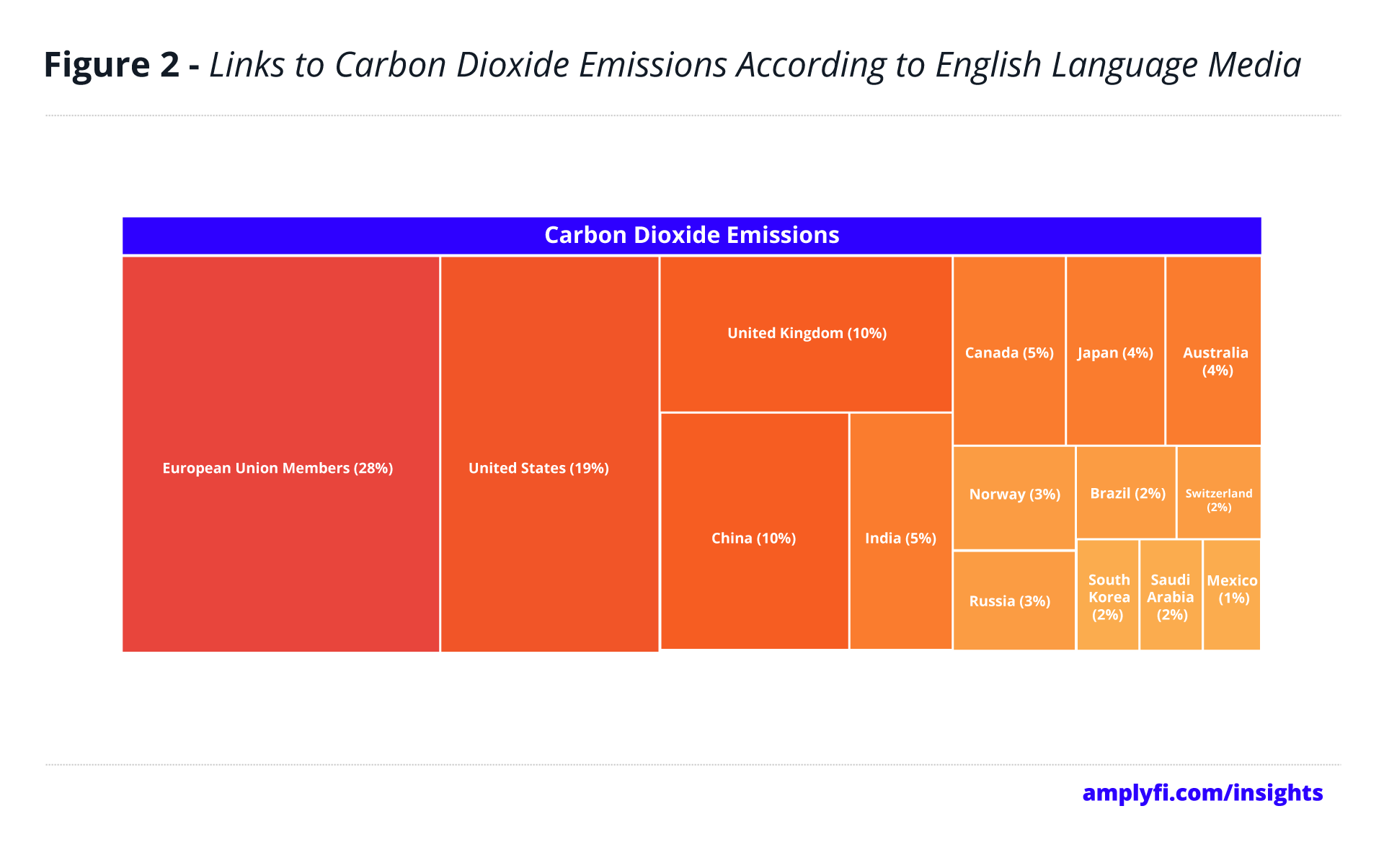

We were then able to compare this data to analysis of global media coverage around the same topic delivered by our AI insights platform. In reading and analysing over 15,000 news items discussing carbon dioxide emissions, our machine was able to quantify connections made by the media between individual countries and the subject of greenhouse gas emissions. In other words, which countries attract the global media’s attention. The results (see Figure 2) indicate that the countries attracting the highest media interest are the EU, US, UK, and China, respectively.

Comparing our analysis to that of OurWorldinData (which shows China to be the world’s largest emitter of CO2) it is clear that there is a disparity between actual reported scientific data and how the media elects to report on the subject. The UK in particular receives a disproportionate amount of media interest relative to its actual contribution to global CO2 emissions. This insight could be concerning as the general public is most likely to have opinions shaped and influenced by what they read and hear in the news rather than from direct reference to actual scientific data. For instance, if we were to rely solely on the media to be informed, we would be forgiven for thinking that the EU was most linked to harmful emissions, therefore potentially the largest source of emissions, when the facts indicate that it actually sits behind China and the USA. Comparatively, the EU attracts 28% of the media’s attention and China only 10%. Taken at face value, this would infer that its actual emissions were three times higher when, in fact, they are nearly three times lower. Such disparities between news coverage and actual data could be damaging, especially when seen with a global issue such as climate change that poses a potentially existential threat.

The EU’s high links to carbon dioxide emissions may correlate with recent events such as a proposed target to have 30 million zero-emission electric cars by 2030 and to ban internal combustion engines by 2035. Since media articles discussing the progress in the electric cars industry compare progress in the EU with strides being made in the US, the same could be said for the United States, the country with the second-highest media links (19%). However, at the same time, China also made similar and very public statements of intent to address climate and yet global news agencies appear to have elected not to report this as strongly.

Furthermore, by narrowing our analysis down to focus on documents published exclusively in the UK, we see a similarly distorted view to that presented by scientific data (see Figure 3). Looking just at UK media documents, we see the perspective outward-looking from the UK to see what foreign countries the nation speaks about.

Whilst our analysis highlights the most spoken about countries in the media in relation to carbon emissions, media coverage being disparate to reality could pose potentially negative consequences. For instance, relying on media presentations, the public may form inaccurate opinions, in relation to how countries are handling CO2 emissions.

COP26 resulted in a number of varied outcomes., For instance, China (along with others) failed to pledge to reduce methane emissions (although CO2 has a longer-lasting effect, methane has more than 80 times its warming power over the first 20 years of reaching the atmosphere) or phase out coal and fossil fuels. India, the second leading emitter in Asia, pledged to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2070, 20 years after most other nations. The EU, despite being the third highest-emitting region, abstained from committing to zero-emission cars. The move was surprising given that the region has elaborate plans to promote the manufacturing and use of clean electric vehicles.

To conclude, the clear imbalance in media coverage of CO2 emissions threatens to create or perpetuate “availability bias” whereby readers begin to connect the likelihood of a particular kind of risk, in this instance the impact of high CO2 emissions, to personal experiences – all reinforced by media mentions. Such an effect will have positive and negative connotations. From a positive perspective, it means that countries and regions with multiple media mentions associated with CO2 emissions will have a stronger impetus to act to address the issue. However, it may also ensure that the action is not necessarily focused where it is geographically most needed.

Accurate, unbiased, and timely information is critical to ensuring that actions to address and reverse the impact of climate change are consistent with the magnitude of the problems at any given geographic location. Whilst the Climate Content Pledge launched at COP26 indicates that the media appreciates the role that it has to play in shaping conversations, perceptions, and policy decisions, the evidence indicates that, at present, it is a long way from achieving the necessary consistency that it promises.