Immersed in a world confronting battles of the wallets, we, as consumers, by all means, have the freedom to make our own choice of consumption. Taking this one step further, “consumer activism” gains its prominence to aim for societal changes. Consumer activism can be understood as “boycotts” against “BUYcotts”, where the former represents consumers not buying specific products while the latter implies consumers’ intentions to purchase a company’s products or service in a show of support. This concept, which can seem simple at surface level, becomes complex once the nature of participants, their underlying thoughts and ultimate goals are unpacked. Using AMPLYFI’s AI-driven research platform, we have unearthed unique insights into the landscape of consumerism. Our technology leverages machine learning and data science to deliver insights by analysing and making connections across structured and unstructured data at scale, uncovering the hidden links, trends and messages inside the universe of consumer activism and builds a comprehensive analysis on top of this data.

Who are the consumer activists? Who and what are they against? Why are they doing so and in what forms? To what extent have they succeeded? With each consumer activity owning unique answers to these questions, our AI-driven platforms can access as wide a scale of information as needed across time and globe, while simultaneously diving deep into this data to dig out details of each individual instance with full coverage across sources such as news, journal articles and academic papers.

Boycotts, buycotts and other forms of consumer activism have always maintained a bold historical presence in the capitalist world where individual customers and workers redressed the imbalances in the marketplace. Academics are active in this space, aiming to trace the concept of a boycott back to Biblical times or earlier, draw comparisons with practices throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries and chronicle the historical experience of the United States (the term “boycott” originated in Victorian Ireland in 1880) in terms of different types of boycotts in different eras. Global examples include a government sponsored buycott in interwar Austria- the Buy Austrian Goods campaign of 1927 to 38, boycotts of Japanese imports in the Chinese city of Tianjin between 1928 and 1932, and the still ongoing Arab boycott of Israel, despite being much diminished in recent years. Recent writings are also focusing more on contemporary topics, such as the development of fair trade since the Second World War and labour rights along the production lines.

For both academics and non-academics, AMPLYFI’s analysis contributes to showing a comprehensive and detailed image of how prominent consumer activism has become in recent years – what has happened and what they are about.

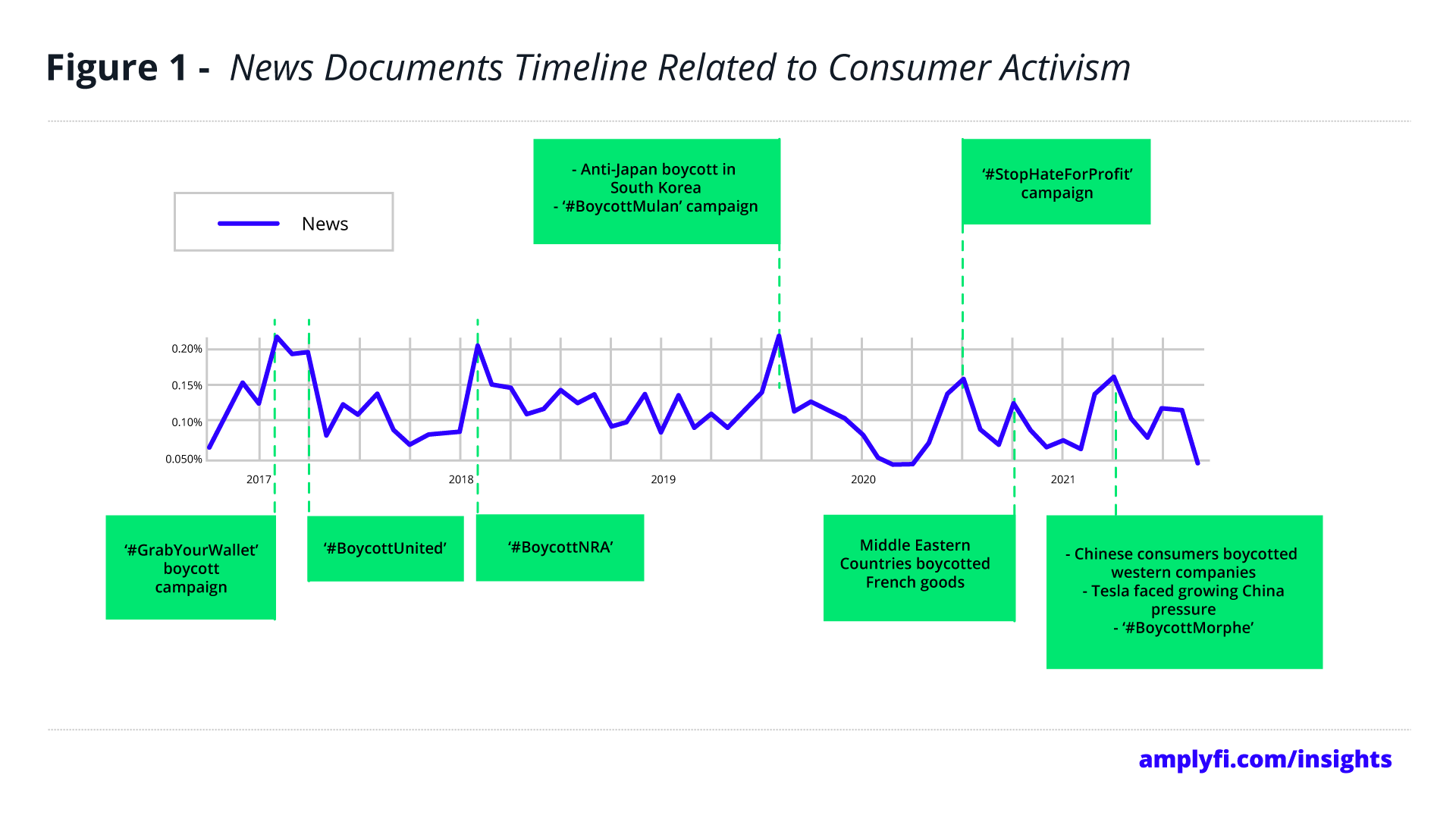

Based on AMPLYFI’s document corpus, the peaks in Figure 1 show when key consumer activism events have happened and the volume of news documents augmented around that event.

In 2017, two big events related to consumer activism occurred. The ‘#GrabYourWallet’ boycott campaign, an economic boycott against companies with connections to Donald Trump, peaked in February 2017 after a lewd conversation between Donald Trump and Billy Bush on the set of Access Hollywood was leaked, alongside a rising ‘#BoycottUnited’ hashtag across social media and late-night television after a video filmed on April 9 hit the mainstream showing David Dao, a 69-year-old Kentucky physician, being dragged down the aisle on a United Airlines flight with blood on his face by three officers after refusing to give up his seat. While the first incident predominantly arose in the United States, the second incident sparked global outrage with social media users across the United States, Vietnam and China calling for a boycott of the airline carrier. To explore the consumer activists’ actions further, our data shows that the February campaign affected the likes of Nordstrom and Uber, as well as Ivanka Trump along with her clothing and shoe line, as consumers enacted the economic boycott.

As seen in AMPLYFI’s analysis, further boycotts emerged in 2018 with the ‘#BoycottNRA’ against the National Rifle Association, a US gun rights advocacy group and its business affiliates. The boycott followed the Douglas High School shooting incident in Florida and the NRA’s criticised response in requiring more armed security to protect against the possibility of future attacks at schools. During this boycott, the corresponding activists were not simply individual consumers, but also large organisations and corporations, such as the First National Bank of Omaha who were among the first to respond.

AMPLYFI’s AI-driven analysis also revealed a peak related to consumer activism events occurred in August 2019. This peak resulted from several events occurring during that time, including South Korea’s anti-Japan boycott against Japan’s tightened control of exports of chemicals, the ‘#BoycottMulan’ campaign which responded to film star Liu Yifei’s support for Hong Kong police in the wake of police violence accusations against protestors and Disney’s credits to several government entities in Xinjiang where the alleged detention camps of Muslim Uighurs and other ethnic minorities have been documented. This time also saw China’s boycott against American farm produce due to the China-US trade war. Other multiple boycotts were undertaken against different brands including Taiwan bubble tea chains, Versace, Coach and Givenchy corresponding to political tensions over Hong Kong issues in the summertime.

Consumer activism had also been prominent throughout 2020. Firstly, the death of George Floyd in May initiated a national reckoning over racism both within the US and across the globe. Against such a backdrop, the ‘#StopHateForProfit’ campaign emerged, enlisting multinationals to help pressure the social media giant, Facebook, into taking concrete steps to stop valuing profits over hate, bigotry, racism, antisemitism and disinformation in its July 2020 ads and turned into a widespread advertising boycott of Facebook. Two months later, middle eastern countries called for a boycott of French goods to protest against President Emmanuel Macron’s defence of the right to show cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad in the aftermath of the gruesome murder of a French teacher who showed the cartoons. In the eastern part of the world, Jordan, Qatar and Kuwait had stripped French products; Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries had called for a hashtagged boycott of French supermarket chain Carrefour; Libya, Gaza and northern Syria had also witnessed small anti-French protests.

Some of the most recent consumer activism events have been mostly around the Chinese market in which western companies faced boycotts from Chinese consumers when expressing concerns over alleged human rights abuses in the Xinjiang province in April 2021. H&M was the main target, yet Nike, Adidas and Puma, which are all members of the Better Cotton Initiative, also suffered consumer backlash. Within the same month, at the Shanghai auto show, activism was also observed when consumers complained about problems with Tesla’s cars and put the firm into a vulnerable position in the Chinese market. Besides, a small part of the news discussed the makeup brand Morphe which had a longtime sponsorship with James Charles, who has been accused of sexual harassment, and got bombarded by the ‘#BoycottMorphe’ campaign.

For a closer look into the contexts and subjects involved in this field, selected key phrases and organisations and their respective trends over time provide greater insights into the underlying reasons and involvement behind the activists’ events.

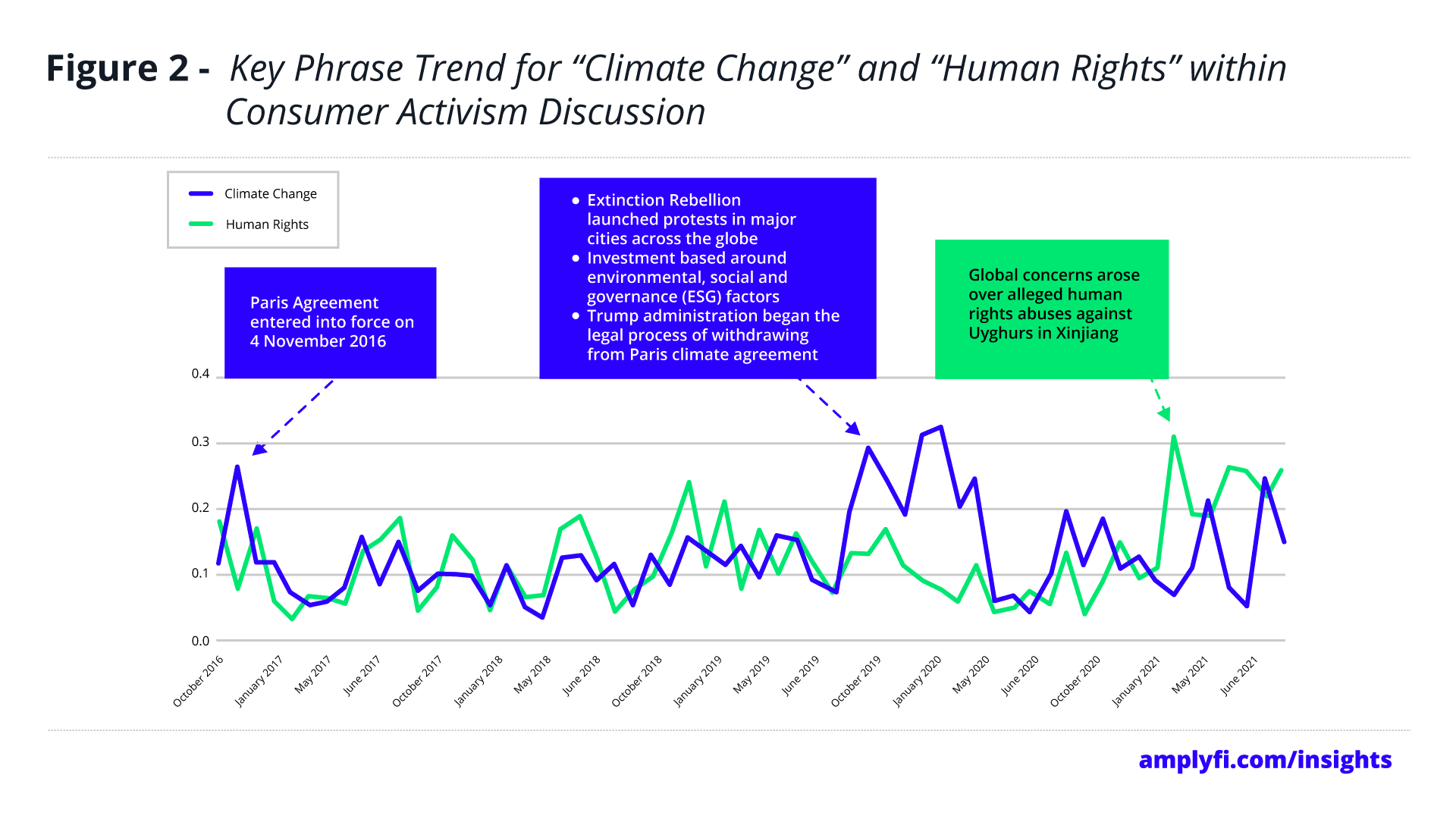

“Climate change” and “human rights” have always been two hot topics across the whole document corpus from 2016 to the present day, and large scales of consumer activism could be linked implicitly and explicitly, shown in Figure 2. The profound peak for “human rights” found in March of 2021 corresponded to global concern over alleged human rights abuses against Uyghurs in Xinjiang. For “climate change”, two identified peaks were November of 2016 and October of 2019. The former marked the month when the Paris Agreement entered into force, whilst the latter witnessed the spread of Extinction Rebellion protests, a global environmental movement, across the globe, the increasing attention around Environmental Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) factors and Trump beginning to withdraw from the Paris agreement. This analysis implies that the origins and contexts of consumer activism based around these two topics could have multi-disciplinary roots including political treaties and decisions, social-based issues and financial considerations. It is also worth noting that since the increase in prominence of ESG and sustainability factors for consumers, there have also been instances of companies engaging in greenwashing to avoid criticisms, such as falsely marketing or overstating a company and its products as being environmentally friendly. Yet, once companies get exposed to greenwashing practices, consumer boycotts can spark further reputational damage. For example, the oat milk brand Oatly faced boycotts after allegations that a private equity firm that owned a stake in the company had also contributed to the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest.

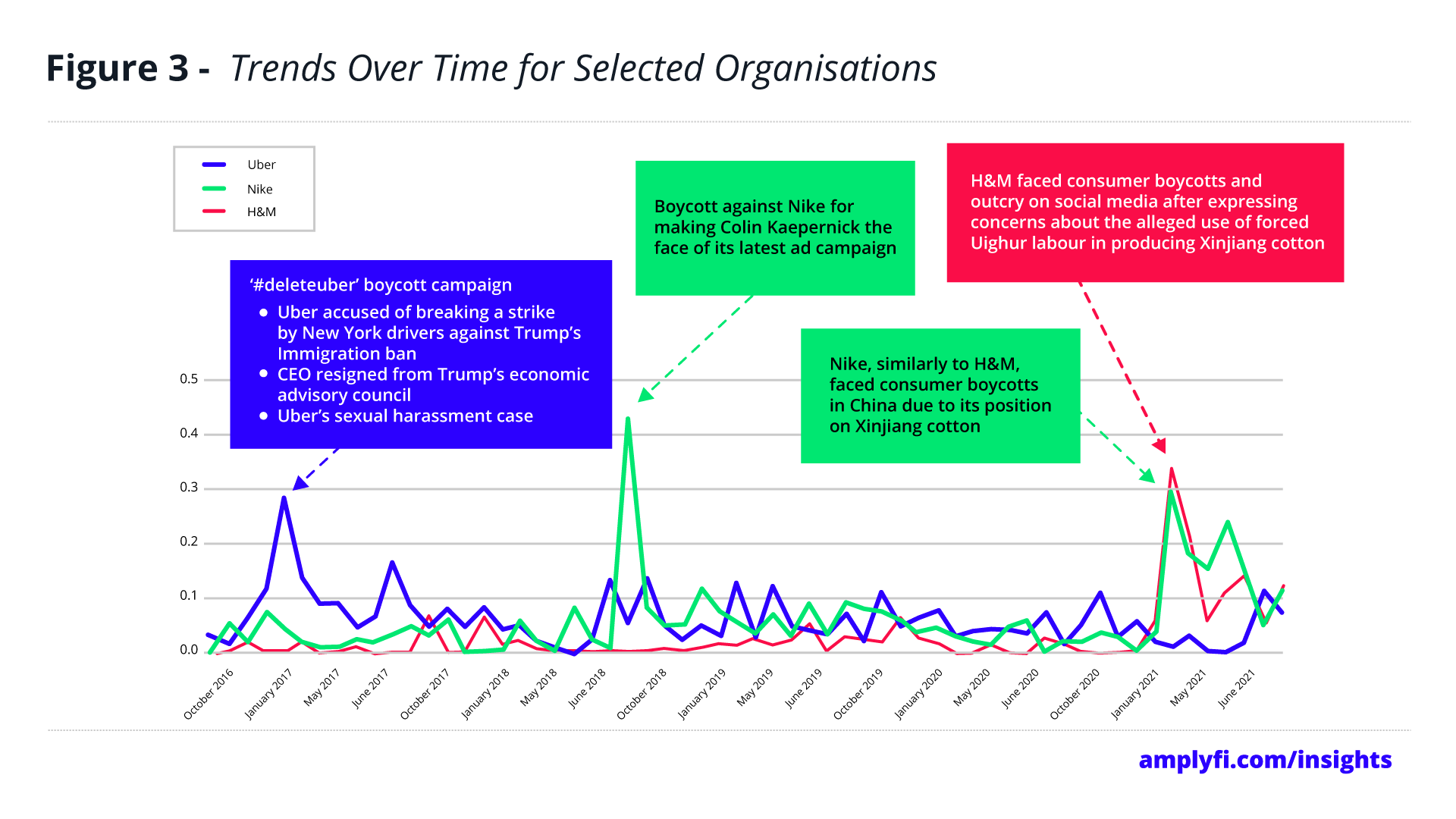

The connections between various organisations and consumer activism are indicated in Figure 3, focusing on Uber, Nike and H&M. Uber’s biggest peak was in February 2017 during the ‘#deleteuber’ boycott campaign, which followed the succession of Donald Trump and the company being accused of breaking a New York drivers’ strike against Trump’s immigration ban. The news surged with Uber’s negative image due to a sexual harassment case and its continued association with Trump, resulting in its CEO resigning from Trump’s economic advisory council. Nike faced a boycott in September 2019 when it made Colin Kaepernick, a former quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers, the face of its latest ad campaign. The figure was controversial with regards to his action of kneeling during the playing of the national anthem at his games to protest racial inequality. He had been accused of disrespecting the anthem, the military and the American flag. H&M had remained especially silent in the public eye until March 2021 after expressing concerns over Uighurs human rights in producing Xinjiang cotton. Being the main target of Chinese consumers for boycotts, it suffered declines in sales and closures of stores in China, along with Nike who as well experienced backlash in consumption.

To conclude, it is clear from our analysis that there have been many trends in consumer activism with respect to different key social, economic or environmental contexts and subjects evolved around particular periods. The prominence of social media today has further amplified the happenings and impacts of boycotts to a greater extent, especially with the help of Twitter’s hashtags giving the power for what would be originally localised events to be seen on the global stage. There is no doubt that consumer activism remains an indispensable element during the 21st century’s battles of the wallets.